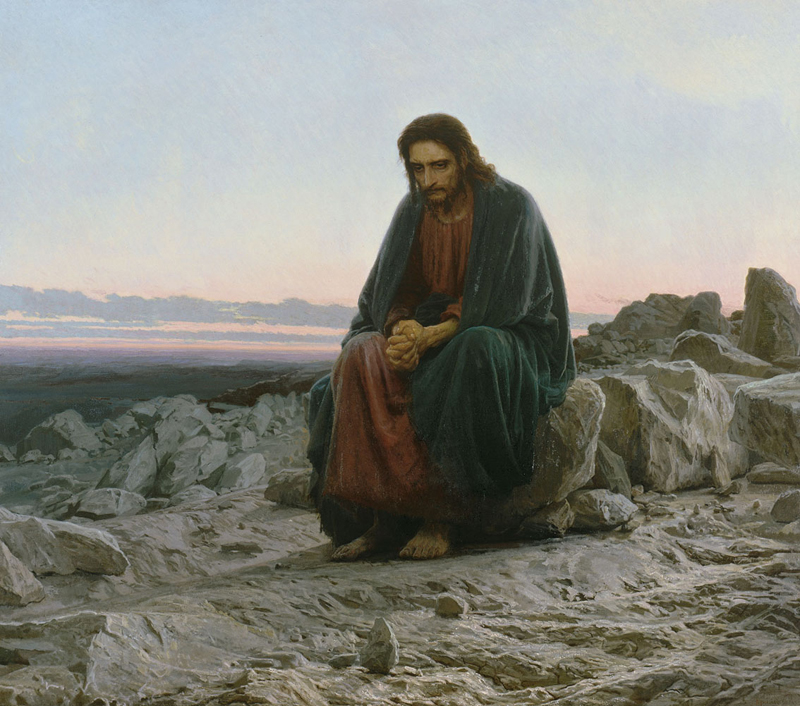

Matthew 4:1 Then Jesus was led up by the Spirit into the wilderness to be tempted by the devil.

1837-1887

Christ in the Desert

Painting

1872

Gosudarstvennai︠a︡ Tretʹi︠a︡kovskai︠a︡ galerei︠a︡

Moscow

Click image for more information.

Commentary by Hovak Najarian

Christ in the Desert, Oil on Canvas, 1872, Ivan Nikolaevich Kramskoi, 1837-1887

During the Renaissance of the fifteenth century, intellectuals believed that some subjects in art were of a higher order than others. “History painting” was judged to be the most difficult and at the highest level. In a broad interpretation of the term, these were paintings that told a story; the category included biblical and historical subjects as well as allegorical and mythological scenes. In history paintings, the figures in them interacted in settings that required an artist to have mastery of all aspects of painting. Ranked below history painting was full figure portraiture (a portrait in the form of a bust was a step lower). Ivan Nikolaevich Kramskoi (also spelled, Kramskoy) was not a painter of historic battles or mythical events, and his work was not in keeping with new trends in European painting.

Kramskoi lived in Russia at a time when France had become the center of the art world. In Paris, his contemporaries the Impressionists were changing the emphasis of painting with studies of natural light, color, and the landscape. Kramskoi was neither a history painter nor part of the Impressionist movement; he painted portraits, in a studio and his colors tended to be monochromatic. Yet, his portraits were of exceptional quality. He had an ability to imbue a sitter’s facial expression with details that gave insights into a person’s mood and character. “Christ in the Desert,” shown here, was not painted for an art-minded Parisian gallery-goer whose interest was in seeing the latest developments in the art world. Kramskoi shows us Christ in deep thought and introspection at a time before being tempted.

After his baptism, Jesus “…was led up by the Spirit into the wilderness to be tempted by the devil.” In this painting, Christ is isolated from all human and cultural contacts as he sits alone among the hard, bare, and colorless stones. He remained in this desolate place without food for forty days and was unimaginably hungry. When Satan determined Christ would be vulnerable, he came to tempt him, saying: “If you are the Son of God, command these stones to become loaves of bread.” Christ turned him away, replying: “It is written, ‘Man shall not live by bread alone, but by every word that proceeds from the mouth of God.’”

In describing this painting, novelist Ivan Goncharov wrote, “…there is nothing festive, heroic, victorious [about the figure in the painting] – the future fate of the world and all livings is concealed in that miserable, small being, in pauper appearance, under the rags, in humble simplicity, inseparable with true majesty and force.”

Hovak Najarian © 2014