Reading: 2 Samuel 5:1-5, 9-10

Commentary by Hovak Najarian

After David was crowned King of Judah and reigned for seven years, all of the tribes of Israel met with him and said, “We are your own flesh and blood. In the past, while Saul was king over us, you were the one who led Israel on their military campaigns. And the Lord said to you, ‘You will shepherd my people Israel, and you will become their ruler’” David then “made a covenant with them at Hebron before the Lord, and they anointed David king over Israel.”

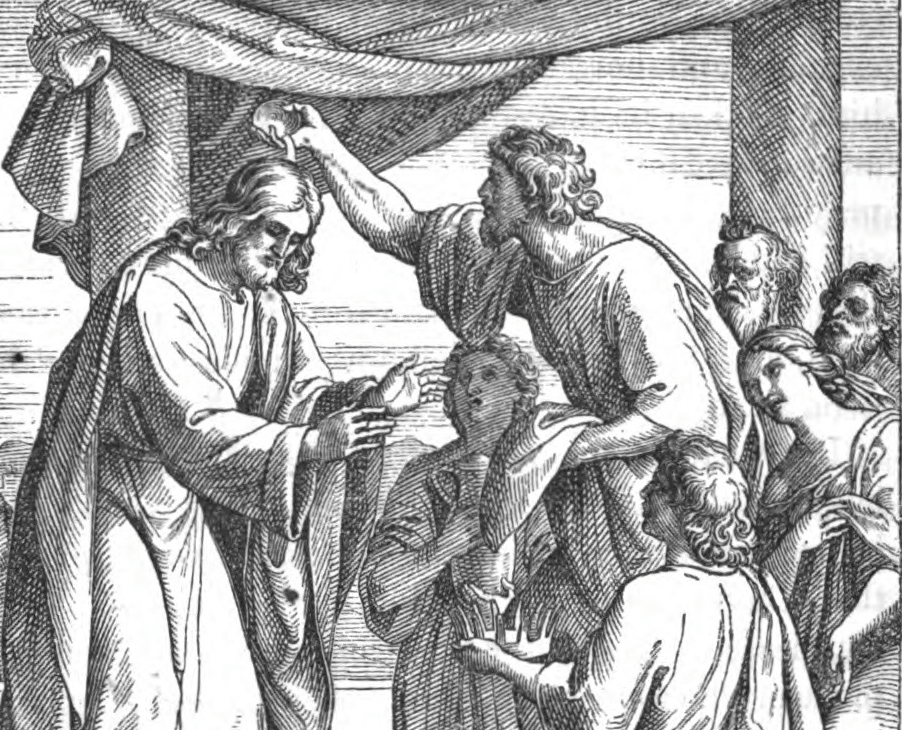

Julius Schnorr von Carolsfeld’s engraving, David Crowned King of Israel depicts an elder pouring oil on David’s head while another is kneeling and holding a crown. David leans forward slightly as he is being anointed. He is looking at the crown and his hands are open as though he is acknowledging and accepting the confidence that is being placed in him.

Carolsfeld presents the moment of crowning as a tableau with David at the center. Almost all attention of the participants on stage is directed toward him. After we glance at the overall composition of this engraving, we tend to go back and enter the scene from the left. From there, the woman at the far left guides us visually to the place above David’s head where oil is being poured. Her gaze is fixed on the procedure. In life, when we see a person’s eyes fixed in a particular direction, our tendency is to look to see what has engaged their attention. This impulse is carried over as we look at subject matter in art. In Carolsfeld’s engraving, almost everyone participating in the ceremony is focused on the anointment.

When we look at shapes, associations come to mind and we project meaning onto them (not always on a conscious level). A pyramid or triangular shape with its broad base gives us a sense of stability, of being secure and on solid ground. Von Carolsfeld has staged the scene of David’s crowning on a stepped-pyramid base, and the central figures move upward from there to continue a triangular grouping with the apex at the point where oil is being poured. Secondary figures witnessing the crowning are on the sides and behind them in the background. Their facial expressions seem filled with emotion and awe. Above them is a drapery, the eighteenth century all-purpose filler of pictorial space and the “go to” backdrop of drama. The clothes of the participants provide an abundance of opportunities for von Carolsfeld, to display his technical skills in the creation of light and shadow effects.

Illustrations enhanced the text of handmade books during medieval times and after printing became mechanized at mid-fifteenth century, they added enrichment to texts through engravings. As the work of artists continued to become specialized, those who created pictures for books became known as illustrators. The art of illustrators was not regarded to be as important as that of painters, but engravers filled a need and they were assured steady work.

German artist von Carolsfeld lived in Italy for ten years and while there he became an admirer of High Renaissance painting. Upon his return to Germany, he had a very successful career as a painter but also produced work in other media. David Crowned King of Israel is one of over two hundred wood engravings created by von Carolsfeld for a Picture Bible

Hovak Najarian © 2018

Art & Music

More about the lithograph process:

Osmar Schindler’s image of David and Goliath is a lithograph [litho: stone, graph: drawing (drawing on stone)]. The process is based on oil and water not mixing. When making a lithograph, a drawing is made with a greasy crayon on a flattened smooth-surfaced limestone. The surface is treated with a weak acid solution which rolls off the crayon drawing and covers the unmarked areas of the stone. After the drawing is removed with a solvent, the surface is made wet. Water clings to the treated surface but not to where the drawing was made (and removed). When the stone is inked with a large roller, the ink is rejected by the watered surface and clings only to where there was once a drawing. Paper is placed over the inked stone and it is run through a press. When the paper is pulled off the stone, the image (once a drawing on the stone) is now on the paper (in reverse). Multiple prints may be made by this process. If color is to be used, a separate stone is used for each color. Artists may color a lithograph by hand after it has been printed. ~Hovak Najarian

For more art and art commentary search the Art & Music Category or use Hovak Najarian as your search term.

Image

See also “julius schnorr von carolsfeld bible illustrations” (Google search)