Matthew 2:13 An angel of the Lord appeared to Joseph in a dream and said, “Get up, take the child and his mother, and flee to Egypt…”

Rest on the Flight into Egypt, engraving, c. 1470-75,

Martin Schongauer, 1430 -1491

Commentary by Hovak Najarian

When Herod learned the “King of the Jews” had been born he was troubled and ordered all males at the age of two and under in Bethlehem and nearby regions, to be killed. Joseph was warned by an angel about Herod’s plan so “he rose and took the child and his mother by night, and departed to Egypt, and remained there until the death of Herod.”

Martin Schongauer’s engraving is based on an account from the non-canonical Gospel of Pseudo Matthew. It tells of a rest taken while the Holy Family was on their journey. After three days, Mary was tired, hungry, and thirsty so they rested under a date palm; Mary looked up at the fruit but could see that it was too high to reach. The baby Jesus said, “O tree, bend thy branches and refresh my mother with thy fruit.” Schongauer depicts five angels bending the tree, thus allowing Joseph to reach the dates. Jesus then asked water to flow from the roots of a palm and the family was refreshed.

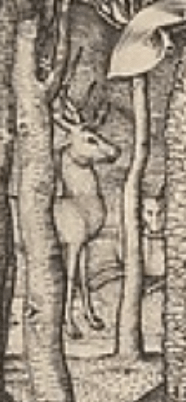

It was a common practice for artists of this period to include symbolic content in their work. Some of the flora and fauna in this engraving may seem gratuitous but in its day their meaning would have been understood. The stag, a symbol for Christ and a destroyer of serpents, is standing watch through the trees in the background. Stags shed their antlers every year and it was believed they renewed them by drinking from a spring; likewise people who drink from the spring of the spirit shed sins and are renewed. A dandelion in the foreground on the right is a symbol of Christ’s passion and a reminder of the future that awaits the child. The lily at the left foreground is a symbol of Mary’s purity, and at the far left is a dragon tree. When the tree is cut it yields a red resin known as “dragon’s blood.”

In Schongauer’s engraving, two lizards are on the trunk of the dragon tree and one is approaching it. The presence of lizards, serpents, and dragons represents the devil and lurking danger. At the very top of the tree is yet another symbol; a parrot. Because a parrot has the ability to fly and talk they symbolize a messenger and are associated with the angel that brought word to Mary that she would give birth to Jesus. In paintings of Mary, a parrot is sometimes placed on her shoulder as though it just arrived and said, “Ave Maria.” When not with Mary, a parrot may be placed high in a tree (as here in the dragon tree) where it cannot be reached by serpents.

More Information

Johannes Guttenberg invented moveable type and printed the Bible not long before Martin Schongauer engraved, “Rest on the Flight into Egypt,” but since most people could not read, art remained an essential means of learning stories of the Bible. During the fifteenth century the range of subjects expanded widely and stories about Mary were enhanced with lore. In addition to events such as the Annunciation and the Nativity, stories based on tradition often were included in illustrations of her life.

Hovak Najarian © 2013, 2020. Post updated 01.02.25

Dragon trees are native to the Canary Islands. It is possible that Schongauer saw one in Leipzig where the first botanical garden in Europe was established.

This scene and folk story from The Gospel of Pseudo-Matthew (scroll down to chap 20) travelled to Europe becoming, with many changes, The Cherry Tree Carol.

The Cherry Tree Carol performed by Joan Baez

This “Art and Commentary” is based on the Gospel [Matthew 2:13-15, 19-23] appointed for the Second Sunday after Christmas, January 5, 2025. After the wise men left Bethlehem (not reporting back to Herod) an angel appeared to Joseph and told him of Herod’s plan to find and kill Jesus. Joseph was told to flee to Egypt with Jesus and Mary and not return until told.

Images

- Web Gallery of Art

- “Dragon Tree” via Google Image Search