Commentary by Hovak Najarian

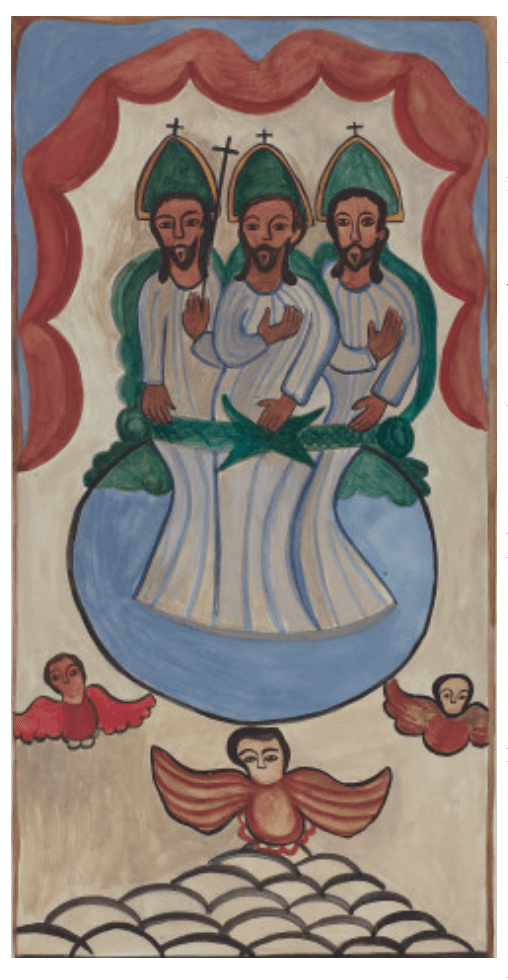

Trinity with Three Faces, Fresco, c.1400, Antonio da Atri, c.1350-1433

The much-quoted statement, “A picture is worth a thousand words,” is true in some instances but not all. A picture cannot represent adequately images such as those that come to mind in the words of the Twenty-third Psalm or the Sermon on the Mount. Art may at times clarify ideas that cannot be expressed by other means but there are times when neither words nor pictures are adequate. A challenge facing early Christian artists was how to create visual images that could communicate concepts found in their faith. A concept such as the Trinity was difficult to explain through art or with words.

In the early Church, there were questions about how (or if) a depiction of God should (or could) be made and if so, what would the image be? God was depicted ultimately as a bearded father figure (possibly derived from the description, “ancient of days” mentioned in the Book of Daniel). A lamb represented Jesus and a dove represented the Holy Spirit. As long as members of the Godhead were depicted as separate entities, artists did not have to deal with the problem of creating an image that represented all three.

The three figures that appeared before Abraham in the Book of Genesis were portrayed as the Trinity but they were shown as separate individuals. By placing them adjacent to each other they were seen as a visual unit. Official use of this form of Trinity was ended by the Pope in the eighteenth century but it continued in places such as the American Southwest.

Another attempt to depict the Trinity is found in the Basilica of Santa Maria Assunta in Atri, Italy. Antonio da Atri’s fresco, “Trinity with Three Faces,” shows Christ standing and facing the viewer. His right arm is raised in a blessing and his left hand is holding a book. To depict Christ as part of the Trinity, Antonio has given the figure one body but three faces. Right and left profiles have been added to Jesus’ head with radiating lines emanating from the halos. As a setting for this composition, Antonio framed his Trinity image in a Late Gothic arch and decorative elements.

Multi-headed divinities existed in other religions and although a three-faced Trinity such as Antonio’s fresco was accepted by the Roman Catholic hierarchy, it was ridiculed by Protestants. It was called the “Catholic Cerberus.” [In Greek mythology, Cerberus was the three-headed dog that guarded the gates of Hades.] As a consequence, in the sixteenth century, the Pope ended the use of the three-faced Trinity but the image remained in remote regions. Pope Innocent XII went further in the seventeenth century and ordered them all to be destroyed. The three-faced Trinity at the Basilica of Atri survived because it was not in sight. It, and other frescos at the Basilica, had been covered with plaster for fear their surfaces might in some way contribute to the spread of the bubonic plague.

Hovak Najarian © 2013

Note: links to the artwork were updated on May 25, 2024; the content was lightly edited. Find additional images of the Trinity with Three Faces using Google Search.

Image: Antonio da Atri, Wikimedia Commons; upload of Retablo of the Trinity, ca. 1936, Watercolor, colored pencil, and graphite on Paper [This is a copy from an altarpiece], E. Elizabeth Boyd, 1903-1974.