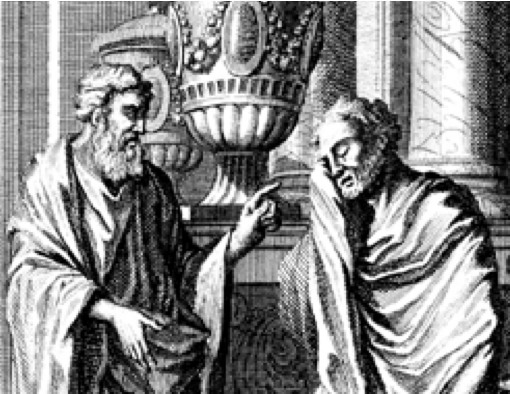

Copper Engraving, Caspar Luiken (1672-1708)

Reading: 2 Samuel 11:26-12:13a

Hovak Najarian

After Bathsheba’s husband, Uriah, was sent into battle to be killed, King David “brought his widow, [Bathsheba] to his house and she became his wife, and bore him a son.” This displeased the Lord and the Prophet Nathan was sent to visit David.

Upon his arrival at David’s palace, Nathan set up his rebuke with a story about two men: one very rich and the other very poor. The poor man had only a ewe he raised from the time it was a small lamb. Like pets that become part of a family, his ewe was dear to him and loved by his children. Nathan noted, “It was like daughter to him.” The rich man lacked nothing and had large flocks of sheep and herds. When he was visited by a traveler, he did not want to give up a single sheep from his own flocks so he took the lone sheep of the poor man to provide dinner for his visitor. The wealthy man used his position to take advantage of the poor one.

When David heard this story he was furious. He said “As the Lord lives the man who has done this deserves to die …because he did this thing and because he had no pity.” Nathan said to David “You are that man.” Nathan reminded David that he had “murdered Uriah the Hittite with the sword of the Ammonites and stole his wife. When faced with the truth, David was remorseful and confessed “I have sinned against the Lord.” He listened as Nathan told him what the sad consequences of his actions would be.

In Caspar’s engraving, David is crownless and his head is downcast. He is standing slump-shouldered as Nathan points his finger at him in a scene reminiscent of a Greek tragedy.

Though Caspar Luiken lived during the early Baroque period, the architectural setting of this engraving gives it a classical quality. Ornate aspects of the print are limited to primarily the drapery, robes, carpet and the two covered storage vessels. In keeping with what was standard practice for an artist of this era, a strong light source defines the folds of the robes and fills the space with high contrasts. Caspar also demonstrates his kill in creating an illusion of pictorial depth. Through an accurate use of linear perspective, our attention is taken back to a brightly lit space and then a window takes us back even farther into a distant landscape.

At the time Caspar Luiken was born, Amsterdam was still aglow from its golden age of art and commerce. During those years it was the wealthiest city in Europe and an important center for the arts. His father, Jan Luiken, was a very successful illustrator and publisher. This was a time before photographs were known; a time when highly skilled engravers such as Jan and his son Caspar filled a need for images that were used in publications. Caspar learned engraving from his father and it was hoped he would carry on the family business but after working with him initially, he went to Germany to be on his own. Six years later he returned to help support his father financially but then he died at the age of thirty-six. A book of Caspar’s engravings of Old Testament events, including Nathan Rebukes David for his Adultery, was published posthumously.

Hovak Najarian © 2012, revised 2024

Art note

A brief description of the engraving process is given in the note following the Art Commentary: “David Playing the Harp before Saul | Art for B Proper 7.”

Happy New Year and Merry (almost) Epiphany! In celebration, these three wise women are stopping by with a gift for you. You might know that some folks celebrate Epiphany (January 6) as Women’s Christmas. Originating in Ireland, where it is known as Nollaig na mBan, Women’s Christmas began as a day when the women set aside time to enjoy a break and celebrate together at the end of the holidays.

Happy New Year and Merry (almost) Epiphany! In celebration, these three wise women are stopping by with a gift for you. You might know that some folks celebrate Epiphany (January 6) as Women’s Christmas. Originating in Ireland, where it is known as Nollaig na mBan, Women’s Christmas began as a day when the women set aside time to enjoy a break and celebrate together at the end of the holidays.