John 20:1 Early on the first day of the week, while it was still dark, Mary Magdalene came to the tomb and saw that the stone had been removed from the tomb.

c. 1170

Marble, height 560 cm

San Paolo fuori le Mura, RomeVASSALLETTO, Pietro

(active 1154-1186 in Rome) Click image for more information.

______________

Commentary by Hovak Najarian

Easter Candlestick, Marble, c.1170, Pietro Vassalletto, (active in Rome from 1154-1186)

In the twelfth century, Europe was in transition from its medieval years to the Gothic period. Several great cathedrals were underway in France but Italy was heir to a long history of Roman engineering and there was no immediate need for change. Additions to churches such as the Basilica of Saint Paul, Rome (San Paolo Furi le Mura) continued to be made in the Romanesque style. This basilica was founded by Constantine in the early fourth century at the site where Saint Paul was buried and is outside the massive walls built around Rome; it is known commonly as “Saint Paul’s Outside the Walls.” [The walls were built by Emperor Aurelian in the third century in an effort to thwart invading Barbarians.] Throughout the centuries, the Basilica of Saint Paul was reconstructed, enlarged, and enriched by emperors and popes. Pietro Vassalletto took part in the extensive construction that took place in the twelfth century.

During the Romanesque period stone masons built churches, made sculpture, baptismal fonts, and fountains, as well as anything else that required carving. There was no debate about whether or not a person was an artist, sculptor, or artisan because those concepts had not entered their thoughts at that time. Stone carvers simply performed tasks that were required according to their abilities; at times they worked on decorative ornamentation and at other times they worked on what we now call, “sculpture.” Often the skills of a father would be taught to his sons and thus several generations would work together. The Vassalletto family of stone carvers remained active between the twelfth and fourteenth century.

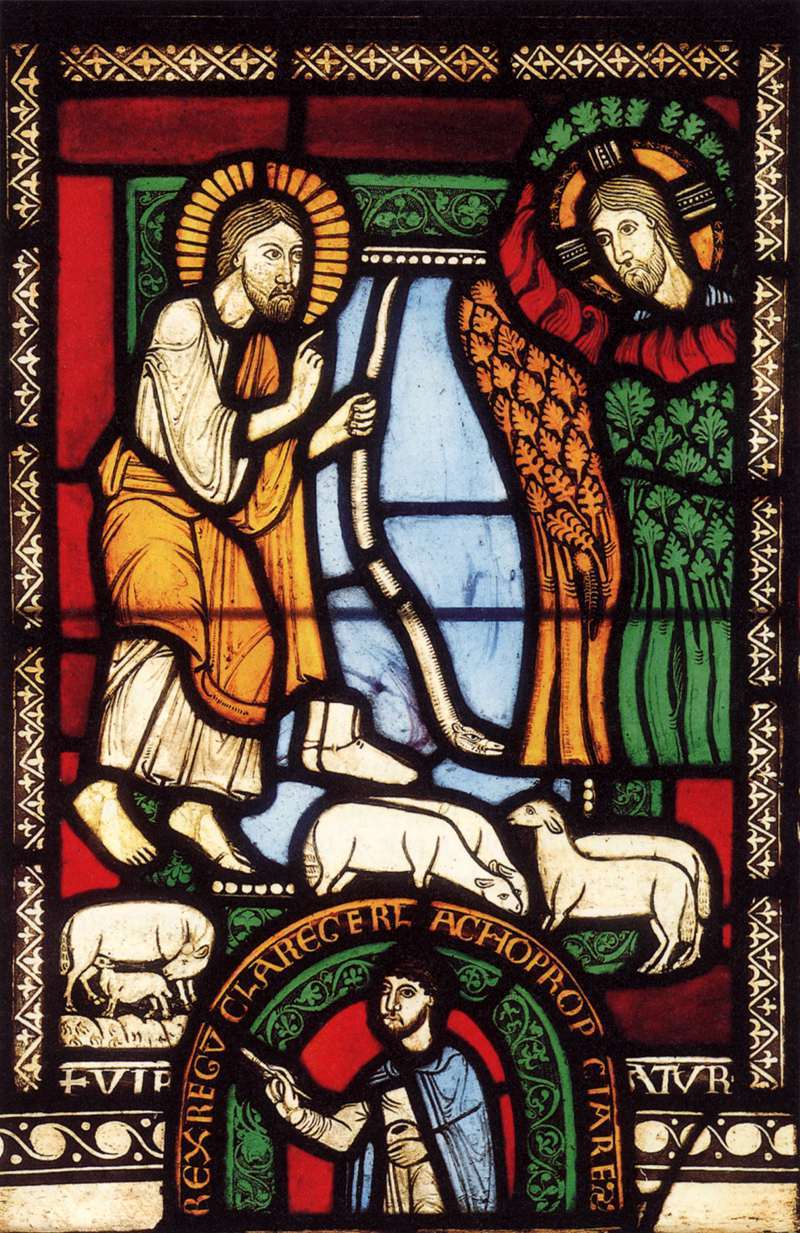

At the Basilica of Saint Paul, Pietro Vassalletto designed and sculpted the colonnade surrounding the rose garden of the cloisters. His columns are not uniformly cylindrical but are twisted in spirals, varied in types of stone and appear light and decorative; they are placed in pairs around the portico facing the garden. For the paschal candle within the basilica, Pietro designed an unusual eight-sectioned candlestick. Candlesticks and paschal candles are made usually taller and larger in order that they may be seen by everyone attending a service. “Candlestick,” however, does not describe adequately Pietro Vassalletto’s eighteen foot tall column that is covered entirely with relief sculpture. Both biblical and secular figures as well as plants and animals are included in its elaborate decorative motif.

Note

The term “paschal” is in reference to “Passover” and among Christians it refers to Easter. It is believed the use of paschal candles started as early as the fourth century; its flame symbolizes Christ as the “Light of the World.” The Candle is marked usually with the Greek letters, “alpha and omega,” in reference to Christ being the “beginning and the end.”

Hovak Najarian © 2013