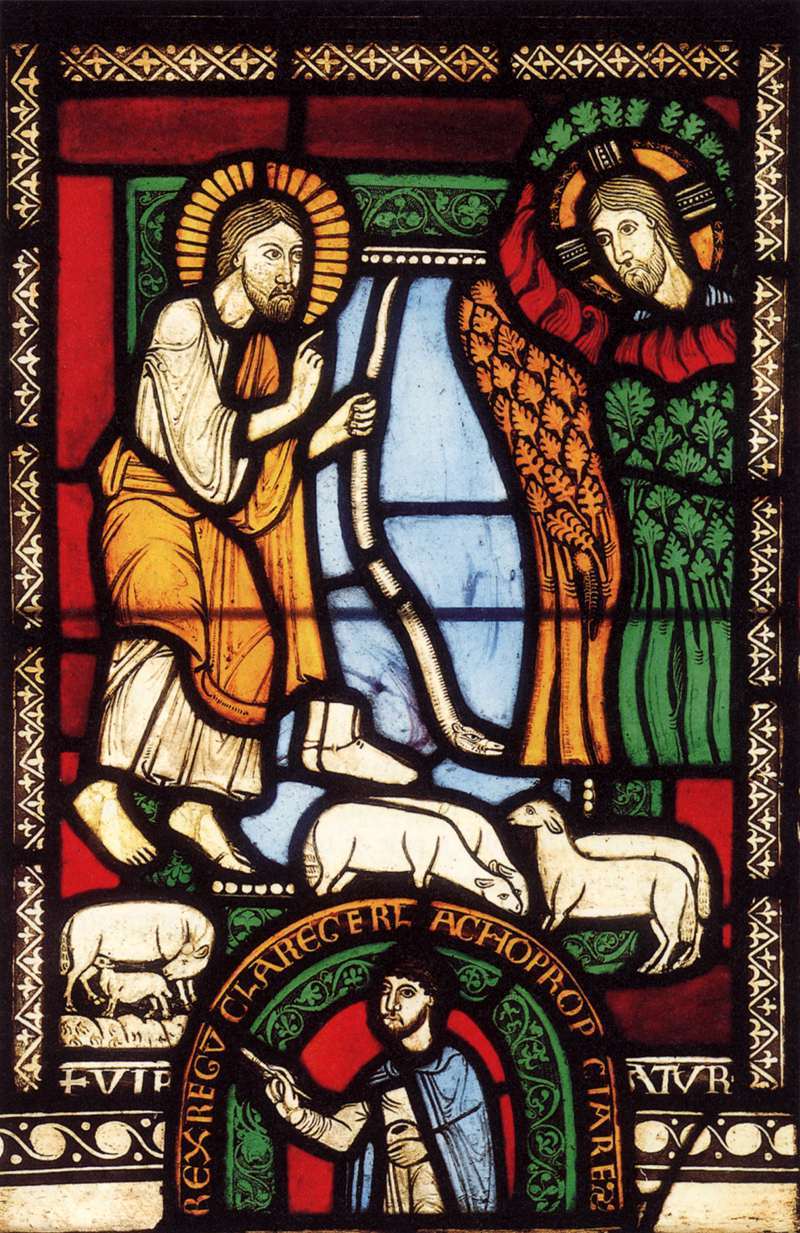

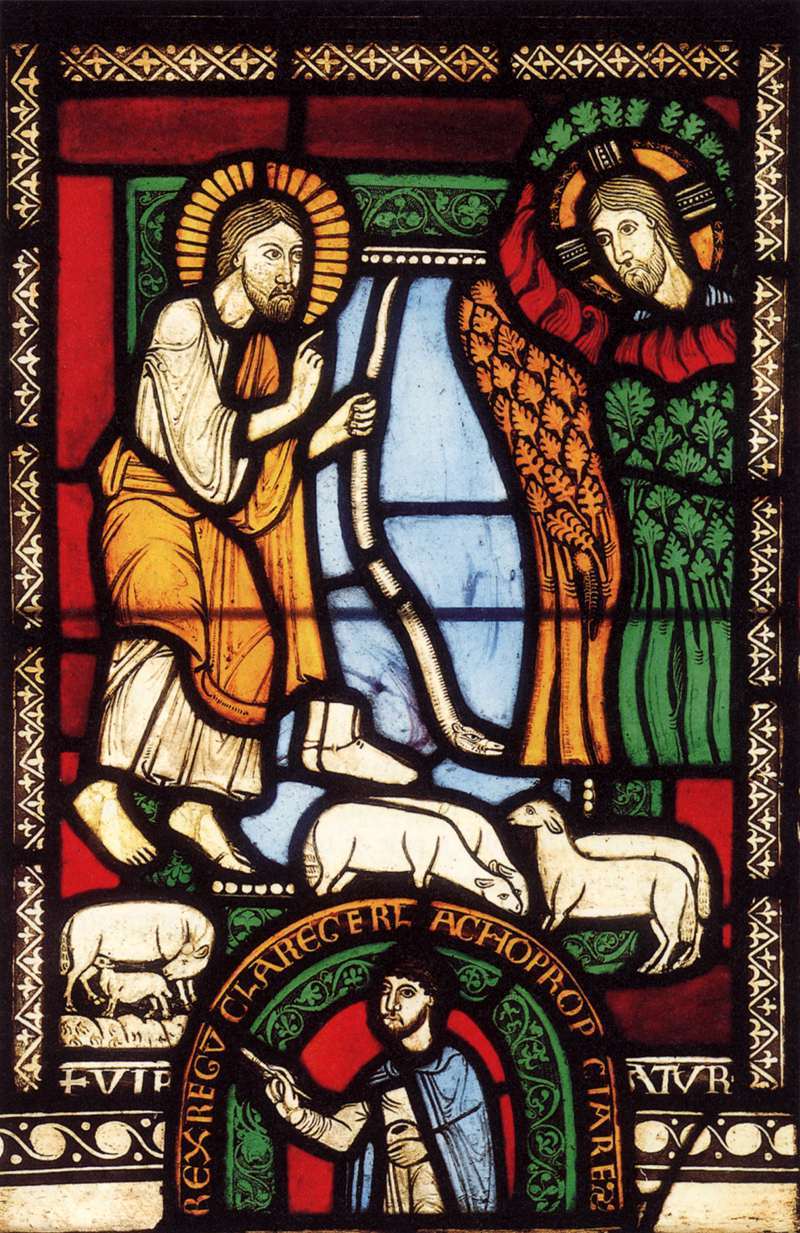

Exodus 3:1 Moses was keeping the flock of his father-in-law Jethro, the priest of Midian; he led his flock beyond the wilderness, and came to Horeb, the mountain of God. There the angel of the LORD appeared to him in a flame of fire out of a bush; he looked, and the bush was blazing, yet it was not consumed

Moses and the Burning Bush (with the artist’s self-portrait), c. 1150,

Stained Glass, Master Gerlachus, 12th century

______________

Commentary by Hovak Najarian

Moses and the Burning Bush (with the artist’s self-portrait), c. 1150, Stained Glass, Master Gerlachus, 12th century

The basic ingredient of glass is silica which melts at a very high temperature (over 3,000 F). The melting point is lowered when a flux is added but for ancient artisans there was still a problem of how to control glass in its fluid state. In the first century BC, a minor industrial revolution occurred in the Near East when a person placed a blowpipe into molten glass, gathered a blob, blew into it, and formed a bubble (like blowing a soap bubble). Artisans learned to attach a pontel rod to where the base of a container would be and then cut the bubble from the blowpipe. While still fluid and workable, the open end (where it was cut from the blowpipe) was made wider to make a bowl or other usable form. The pontel then was snapped off and the glass was cooled slowly as it became a solid. During the late Romanesque period, artisans such as Gerlachus were heirs to a great deal of empirical knowledge which included how to make sheets of glass by cutting elongated bubbles lengthwise then opening and spreading them flat.

Today, the term “stained glass” is used interchangeably with “colored glass” but they are not technically the same. Colored glass contains coloring agents (oxides) within it, whereas staining is done by painting an oxide onto the surface to add details. After sections of glass are painted, they are returned to a furnace and the stain is fused. Then, H-shaped strips of lead called “came” are used to surround each section as a window is being assembled. The came is soldered where their ends touch to hold the glass in place.

“Moses and the Burning Bush” is one of a series of windows depicting the life of Moses; in it, the black, even-in-thickness came can be seen as outlines between the large sections of glass. Details such as the faces of Moses, God, the artist, their clothes, and the burning bush, are all stained by being painted with iron oxide and then fused to the glass. Instead of using many small pieces, Gerlachus’ windows were made from large sections of colored glass on which he painted clarifying details of his subject.

Note

While Master Gerlachus was working in Germany, Abbot Suger began rebuilding the Abbey Church of St. Denis in France. Abbot Suger called for stained glass to be used much more than it had been used previously. Light entering the church through stained glass not only displayed brilliant images that were related to a parishioner’s faith but also the colors were a sensual delight. In defense of its use, it was pointed out that light represented the divine and light coming through glass symbolized the Holy Spirit which was capable of passing through solid objects. The Abbey Church of St. Denis set in motion the direction that was taken by builders during the Gothic Period that followed; a time when there was even greater use of stained glass.

Hovak Najarian © 2013