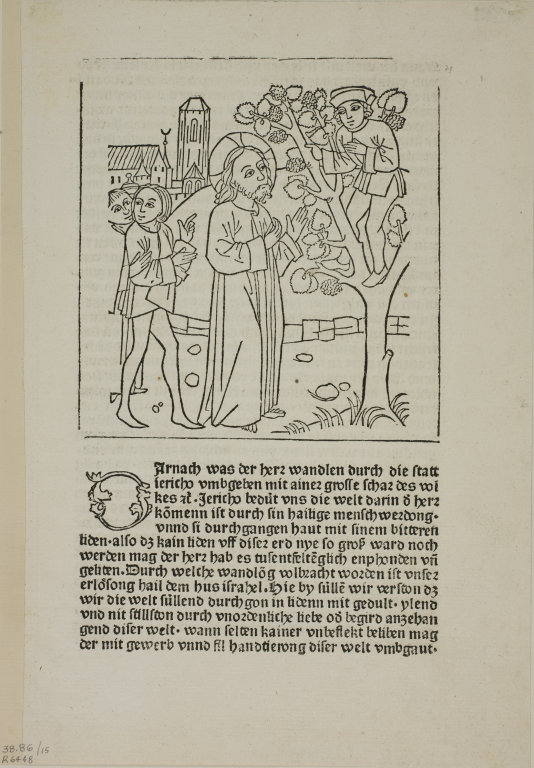

Luke 19:5 When Jesus came to the place, he looked up and said to him, “Zacchaeus, hurry and come down; for I must stay at your house today.”

Jesus Calling Zacchaeus

a woodcut made by and unknown artist

Click the image for more information

Commentary by Hovak Najarian

In the early 1450s, Johannes Gutenberg of Mainz, Germany, developed a successful printing press with moveable type. The technology spread rapidly and within a few decades Gutenberg’s invention was being used at other cities in Europe. In Ulm, (about 135 miles from Mainz), Johann Zainer set up a press to publish both sacred and secular books. Among them was, The Spiritual Interpretation of the Life of Christ, c. 1485.

With the invention of moveable type, it was no longer necessary to hand-letter a text but readers of the day were accustomed to seeing illustrations in a book. Publishers met this expectation with woodcuts. An image, carved in relief on a block of wood and set in place, could be inked and printed together with the text. The time of hand-painted illustrations, as in a codex, had passed. For special editions, however, woodcuts often were colored by hand after being printed.

Included in Zainer’s illustrated book about Christ’s life is, Jesus Calling Zacchaeus. It is a composition that may have been based on a contour drawing made originally as a study for stained glass. This image depicts an occurrence at the time Jesus was passing through Jericho while on his way to Jerusalem. Because of the crowd, Zacchaeus, a wealthy tax collector and a man of short stature, was unable to see Jesus. In order to have a higher vantage point he climbed a nearby sycamore tree. Jesus saw Zacchaeus and spoke to him by name.

In this woodcut, Christ is the central figure and is greater in size in keeping with the practice of depicting important people to be larger than others in a composition. Two people follow Jesus but the crowd that is noted in the Bible, is not shown. Instead, attention is on Jesus at the moment he arrives at the tree where Zacchaeus is perched. One of the figures behind Jesus spots Zacchaeus and turns to a person next to him and points, perhaps saying, “Look, there is a man in that tree!” Jesus’ left hand is raised to greet Zacchaeus, while his right hand motions for him to come down. “Zacchaeus, come down immediately,” Jesus said, “I must stay at your house today.” Zacchaeus welcomed Jesus to his home but the crowd was dismayed that Christ would choose to stay with a tax collector.

While with Jesus, Zacchaeus was repentant and offered to give half his possessions to the poor. If he had cheated anyone, he said, he would repay them four times the amount. Jesus responded, “Today salvation has come to this house…”

Note: The sycamore tree mentioned in the Bible is related botanically to fig trees. It is not of the same specie as the familiar sycamore in America or the maple-related tree in England. This tree, often called, “sycamore fig,” has edible fruit and has been cultivated in the Holy Land since ancient times. The above woodcut is unusual in that clusters of figs have been included among the leaves of the tree.

Hovak Najarian © 2016

(RNS) Reformation Day is mainly marked by Lutherans and members of the Reformed Church, and in some churches it has developed into a holiday meant to rival Halloween. But does it? Let us ‘Splain . . .

(RNS) Reformation Day is mainly marked by Lutherans and members of the Reformed Church, and in some churches it has developed into a holiday meant to rival Halloween. But does it? Let us ‘Splain . . .