VASARI, Giorgio

VASARI, Giorgio

(b. 1511, Arezzo, d. 1574, Firenze)

Click to open Web Gallery of Art Artist Biography and to explore other works by this artist.

Annunciation

1570-71

Oil on poplar panel, diameter 157 cm

Móra Ferenc Múzeum, Szeged

Click to open Web Gallery of Art commentary page. Click image again for extra large view.

Annunciation

1570-71

Pen and wash, squared with black chalk, diameter 133 mm

Pierpont Morgan Library, New York Click to open Web Gallery of Art commentary page. Click image again for extra large view.

Separated, misidentified and now united by scholarship.

Annunciation, oil on panel (1570-71), Giorgio Vasari (1511-1574)

by Hovak Najarian

During the High Renaissance of the late fifteenth century, men such as Leonardo da Vinci and Michelangelo had what seemed to be unlimited skills. The term Renaissance man is used even today to designate a person with knowledge and impressive skills in several disciplines. Although Giorgio Vasari was born in the early sixteenth century and missed being a part of the High Renaissance he was a person with a wide range of interests and skills. In that respect he was very much like the generation before him. Today, however, he is remembered primarily for his architecture and the biographies he wrote about Italian artists; his paintings have lost favor.

The art between the High Renaissance and the Baroque period – starting near the end of the sixteenth century – is not clearly defined; for lack of a better term, historians have called it “Mannerism.” Artists of this period painted in a variety of styles; some of it expanding on or “in the manner” of Renaissance ideas and others tending toward an anti-classicism. Often there would be exaggerated perspective, dramatic lighting, and an absence of the statuesque poses that were part of Renaissance painting. Vasari’s Annunciation was painted during the latter part of the Mannerist period and like the work of Raphael, his figures are classical both in the carefully delineated contours and in their faces. Yet, Mary’s pose and that of the angel Gabriel are in keeping with the theatrical presentation found in Mannerist painting.

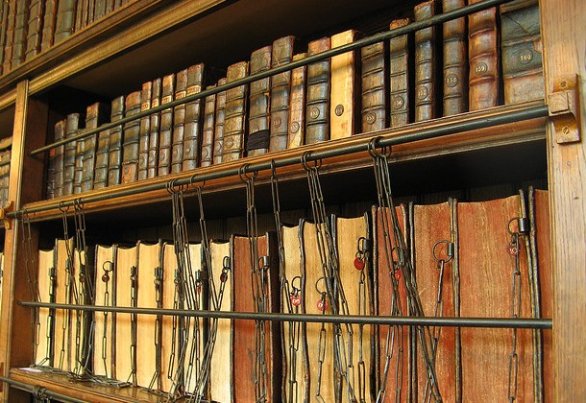

In Vasari’s preparatory ink and wash study we can see he modified his original idea when he made his painting. In the study, Mary is at a reading table (at the bottom center of the drawing) with her finger on a book and there is surprise on her face as though this is the moment when she looked up and realized she had a visitor. In the painting, the book has been shifted out of the way to a stand on the far left side (Mary’s right side) and her extended left hand is now simply making a graceful gesture. Her face is slightly downward and her eyes are downcast to indicate she is within herself in this serene moment. In both the study and the painting, her right hand is on her heart. Gabriel is hovering nearby with arms folded. In his hand he is holding a lily, the symbol of purity.

Symbols were used widely in the art of ancient cultures and many of them were carried over into Christianity. Halos (or a comparable glow) and wings were incorporated into Christian art as early as the third century. The Bible does not say angels had wings but artists added them; now they are standard identifying features. Unlike the large gold-leafed halos of the fourteenth century, Vasari’s Mary is given a delicate transparent circle. She is dressed in the colors blue and red; both are muted in tone. Blue represents heavenly grace and red symbolizes the Holy Spirit. In paintings, Mary often is dressed in blue. Gabriel is clothed in yellow and white; yellow represents light and white represents purity, innocence, and virginity.

In Christian art, figures in a painting often exist in a different reality where the source of illumination is not sunlight or artificial light but rather a light that emanates from a holy figure such as Christ. In Vasari’s Annunciation, the light source is the dove representing the Holy Spirit.

Vasari worked consistently for wealthy patrons and a painting such as the Annunciation was not made for working class people. Like much of the art of the High Renaissance and the Mannerist period, it was painted to be “fine art” for a sophisticated audience.

______________

© 2012 Hovak Najarian