The Angel of Death and the First Passover,

engraving, c. 1897, C. Schonhew, 19th century

Commentary by Hovak Najarian

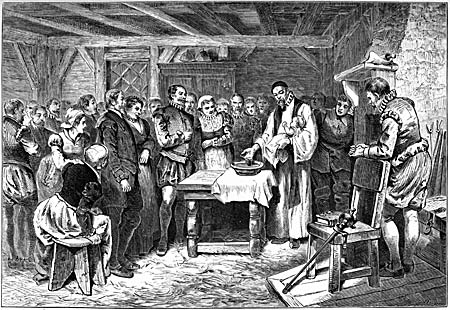

When the time came for the Israelites to leave Egypt and be free from slavery, Moses and Aaron were told about the Passover. God gave them specific instructions with regard to what the people of Israel were to do. A lamb was to be killed, prepared, and then eaten. Blood from the lamb was to be placed on the lintel and door posts of each home. If doors were not marked, the firstborn child and animal of the home would be struck down. C. Schonhew’s engraving depicts the angel of death casting an ominous shadow as it glances at a door to see if it has been marked. Within the home, a Hebrew family is preparing to partake of the Passover meal.

In this engraving, we are attracted first to the activity of an angel patterned after a classical goddess. If she were without wings, had a bow and quiver, and in a wooded area, she could pass easily for the Roman goddess, Diana. To the left, a sphinx seems to be observing the angel as it passes by with sword in hand. The dead figure near its base indicates the person’s doorway was not marked. In addition to the sphinx, references to Egypt are in the background. An obelisk and a wall with marks suggesting hieroglyphics inform us of the culture in which the Passover took place. The tip of a pyramid is beyond the wall.

To the right of the angel is a less active scene. Through an arched opening we see a family gathered solemnly around a table. A tray with a roasted lamb is in the center and the head of the family is leading them in their first Passover meal. They seem to be unaware that the angel of death is passing by their home at the very moment. In order to present separate activities simultaneously, Schonhew divided the engraving into two contrasting areas. On the left, the angel is in motion. There is a sense of urgency about her movements and she is surrounded by dramatic lighting. In contrast, figures on the right are standing still with heads bowed.

The architecture of the interior is in keeping with the exterior but in order to present a direct view of the family, Schonhew departed from two point perspective by aligning the arched wall with the picture plane. This frames the scene and separates it to focus attention on the family. At first glance it may seem we are viewing the interior through a “picture window” but plate glass was not available until the seventeenth century. During the time of Moses, windows would have been simple openings in the wall with no glass.

Note: The Angel of Death and the First Passover, was one of four hundred illustrations in Charles Foster’s book, Bible Pictures, and What They Teach Us (1914). Many of the artists responsible for the work published in Foster’s book were not identified. Schonhew’s name is known only because he signed the above work. Efforts to locate biographical information about Schonhew have not been successful.

Hovak Najarian © 2017

Be well. Do good. Pay attention. Keep learning.

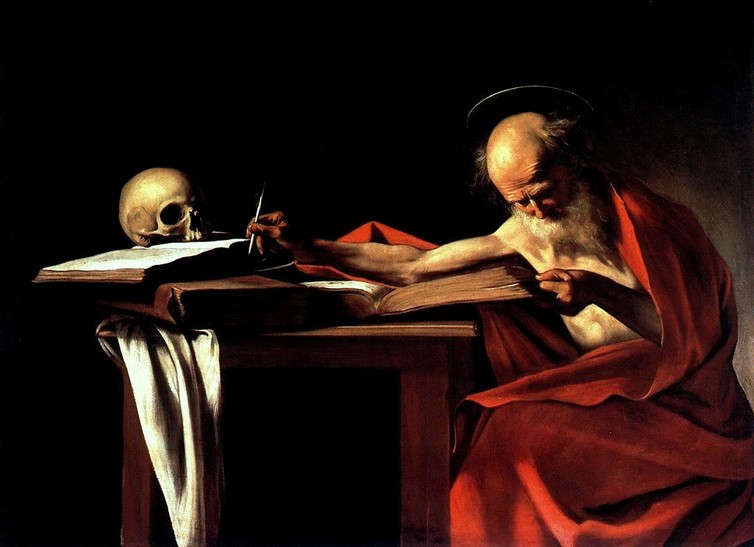

David Playing the Harp before Saul, 1530, Engraving, Lucas van Leyden (1494-1533). In a note attached to this post, Hovak describes the process of engraving.

Artemisia Bowden

Artemisia Bowden